The machinery of UNOC

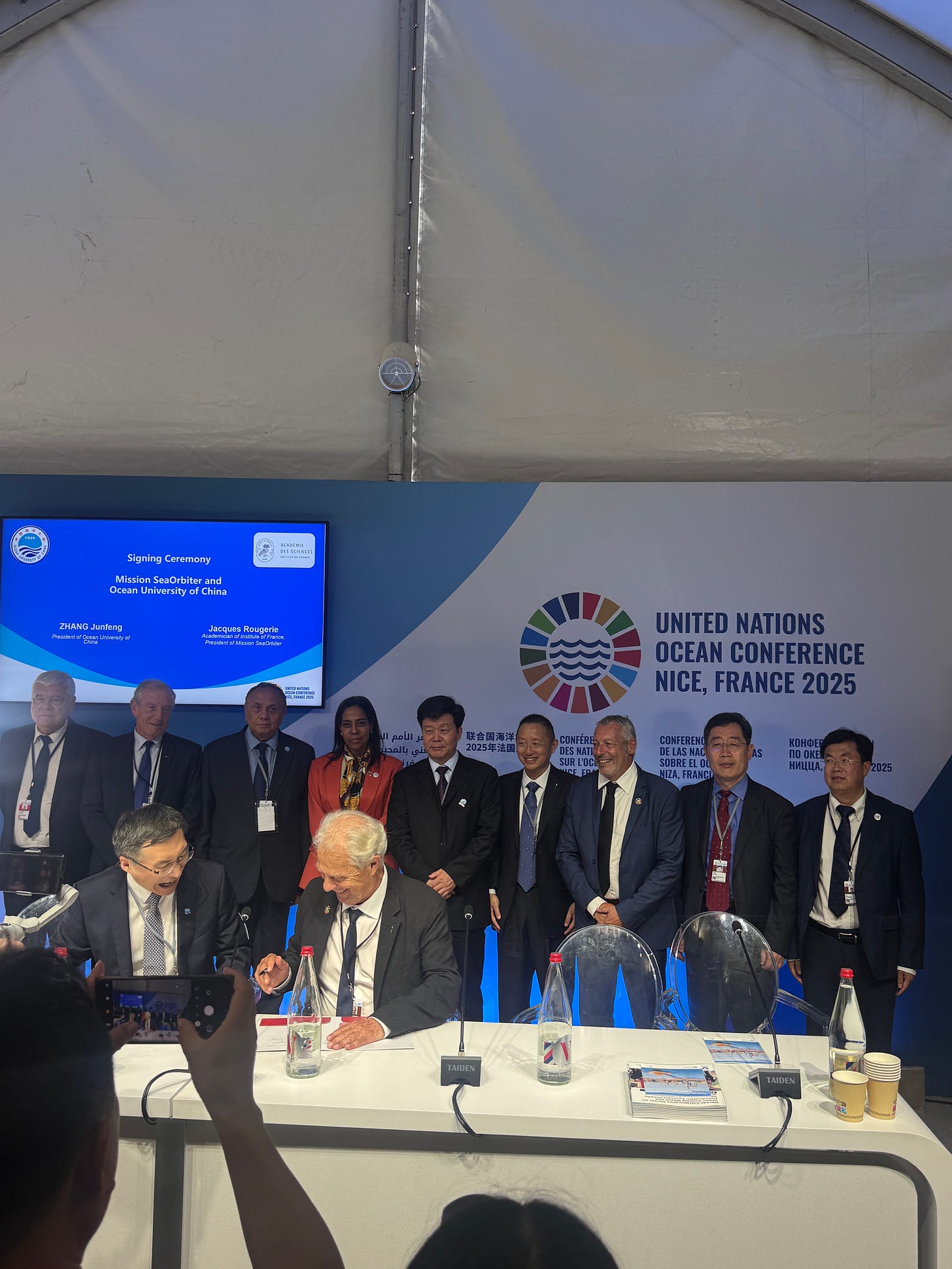

UNOC, the United Nations Ocean Conference, whilst coordinated in all the ways you’d expect, was an interpersonal maelstrom under the surface . Watching diplomats in suits brush past the entrepreneurs in their sandals catching eyes with the determined gaze of the activists, all of it immortalised by the filmmakers.

The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea describes the ocean as the ‘Common heritage of mankind’ and, indeed, there was a sense of collectivity and change (albeit met with caution). The UK has opened a public consultation on outlawing bottom trawling within 41 of its Marine Protected Areas, a move echoing a broader shift in ocean governance. The High Seas Treaty has 51 nations who have ratified it, meaning it edges closer to becoming binding international law and protecting 30% of the world’s seas by 2030. Ninety-six countries have united in calling for an ambitious and binding global agreement to combat plastic pollution. In a powerful rebuttal to the Trump Administration’s unilateral and pro deep-sea mining stance, 37 nations have reasserted their support for a global moratorium and the authority of the International Seabed Authority. Meanwhile, in a significant legal triumph, the EU General Court upheld crucial protections for fragile deep-sea ecosystems, reinforcing the ban on destructive bottom trawling.

Despite all of this, I had a lurking and unsolicited agenda; I wanted to question the conference itself. I wanted to get to the root of what diplomacy in crisis is and whether it even works. I asked politicians and philosophers and business beginners and moguls the same question; does diplomacy like this unlock the change we need and if not, why not? Are these treaties becoming real instruments of change, or just aspirational ‘paper promises’?

The actual policy making wasn’t the main result I’d say. It was the unquantifiable networks formed and the transferral of funds towards NGOs and startups that will happen as a result after the conference finishes.

Can we really be effective when an economist who spends his life quantifying the financial value of a whale using equations out of the Wall Street playbook sits next to an indigenous leader fighting to grant legal personhood to whales?

When we hit crossroads in international diplomacy, we need to:

Stop the hyper-perfectionism inherent to modern diplomacy.

Not every utterance needs to be a polished and pithy social media statement. Negotiation by its nature should be about back-and-forths, correcting and reworking and rewriting and even if the result is messy, its existence is preferable to nothing.

We need to humanise international frameworks.

At conferences like this, even at the highest level in the plenary sessions, personal tensions, desire for self-determination, vested interests, political, philosophical and religious agendas and petty disputes prevail… or are even amplified. At the international level everything is just talk. It is at the national level that change occurs.

Confront the uncomfortable reality that change relies on redirecting subsidies

We need to completely reform the structure of funding so subsidies are repurposed from destructive practises into conservation funding for SDG 14 and small-island developing states.

There are drawbacks; why does bottom trawling remain absent from legislation on Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)? What’s the point of expanding protected areas if destructive practices are permitted within zones designated to protect life and if destructive hotel developments are permitted within areas designated to endemic and threatened species? To ride the trajectory to success, we need to be creating 85 new marine protected areas daily and currently 2.7% of the ocean is effectively protected. Despite this, and although I spent a lot of the time questioning one of the few frameworks we have right now to affect change, Amanda Vincent, the marine representative on the IUCN's International Red List Committee, reminded me at the end of the conference that you can stay busy and cynical, skipping from event to event and finding the flaws in them, but it will always be more effective to choose a lofty objective as your guiding star and then stay focused on what you can do within that orbit. She said anyone who is persistently cynical doesn’t understand that policy isn’t affected at these conferences, it is in the peripheries before and after that the nitty gritty happens.